When writing or recording history it is always useful to understand that what you capture will in no way come close to being the definitive record. History or the telling of it is not some long-dead event frozen in the past, but an evolution of material and artifacts unearthed through ongoing research and the openness of others to share.

In many cases–and sometimes frustratingly so–new relevant material drops onto your lap once a book is published, arriving in the form of an envelope or email from someone who has read the book and would like to share a treasured old letter, diary, or in the case of Terry Harcombe, her grandfather’s logbook from the First World War.

The logbook, which is more of a diary, was compiled by English-born Leslie S. Greenhill and it is remarkable for how well it sheds light on the Chinese Labour Corps’ dangerous and secretive journey from northeastern China to Canada and onto war-torn France. This is the very stuff of my 2019 book Harry Livingstone’s Forgotten Men: Canadians and the Chinese Labour Corps in the First World War. I’ve purposely kept the quoted material exactly the way it was written.

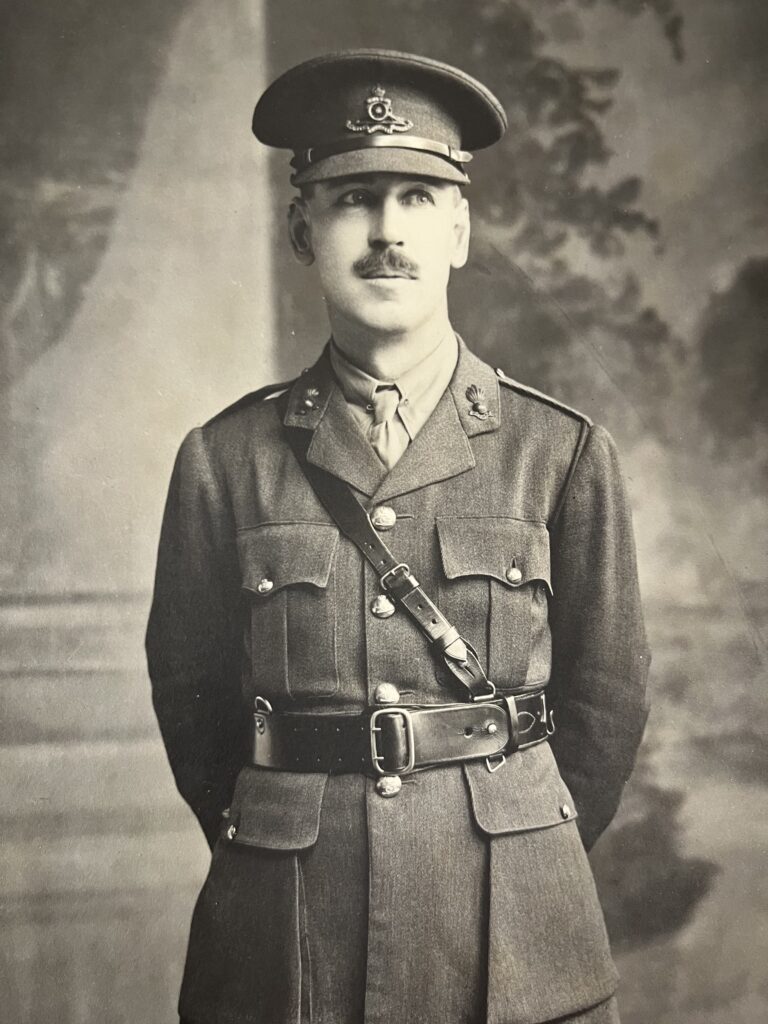

Greenhill was a thirty-seven-year-old bachelor working as secretary of the Hong Kong Land Investment Agency when his life took a sharp turn. The junior officer in the British Army reserve was dispatched from the then-British crown colony to the CLC manning depot at Weihaiwei in northeastern China. His orders were to help escort some 2,400 members of the CLC. Not only would Greenhill travel with the contingent across the stormy Pacific on the Empress of Asia, he would cross Canada by rail on a CPR-CLC special, and eventually onto Liverpool via Montreal and Halifax.

Along the way there were deaths at sea, an on-board riot as the ship reached Vancouver, and more trouble after the contingent reached the East Coast.

Part 1

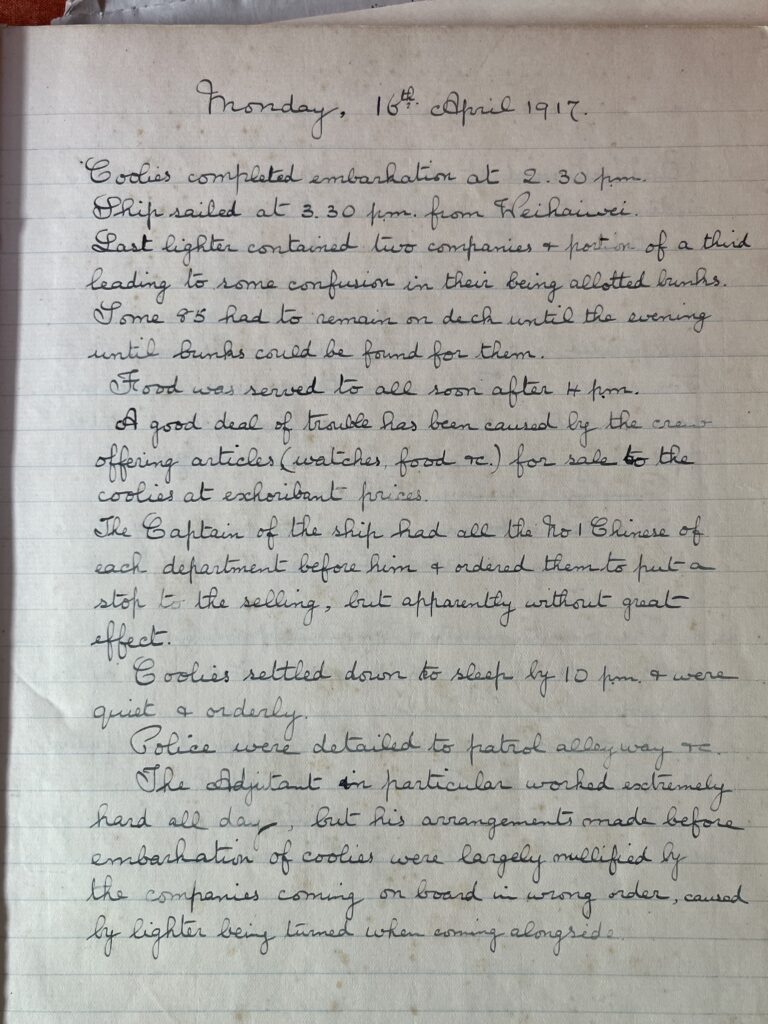

The logbook begins on Monday, April 16, 1917, at Weihaiwei when Greenhill writes that the embarkation of the Chinese labourers or “coolies” is completed by 2:30 p.m. An hour later the Empress of Asia departs amid confusion owing to the number of men who came aboard in the wrong order and the hasty allotment of available bunks in steerage. “Some 85 had to remain on deck until the evening until bunks could be found for them.”

Food was doled out to the men at 4 p.m. “but a good deal of trouble has been caused by the crew offering articles (watches, food, etc.) for sale to the coolies at exorbitant prices. Police patrolled the ship’s decks and alleyways, but by 10 p.m. the labourers had settled down to sleep…and were quiet and orderly.”

Breakfast was served at 8 a.m. on the 17th and throughout the day the distribution of food went well thanks to a tally system introduced by the ship’s steward. Selected Chinese labourers, who Greenhill refers to as “lance corporals”–each in charge of 140 men–were paraded and handed a tally ticket for the meal about to be served. The men also received updated instructions that were to be passed on to those in their charge.

Meanwhile, the selling of various articles smuggled on board continued despite the crackdown. There was also a problem with the stores or supplies taken onboard. “Unable to open the canteen as the packages of stores shipped were not adequately marked & had to be sorted out. The Quartermaster and officer appointed to take charge of canteen were busy sorting stores until after 10 p.m.”

At Nagasaki on the 18th, Japanese quarantine officials boarded and the labourers were lined up and examined. “This was carried out by sending all onto the promenade deck & examination took place chiefly at the after hatch (rear of the ship)…. Three coolies found to be sick.” Soon one of the conducting officers became ill. “Mr. Forbes was seized with what the ship’s doctor said was an epileptic fit.”

Greenhill noted that while still at Nagasaki, sampans came alongside “and without the aid of a police boat it was impossible to prevent the selling of oranges, apples & other articles.” He also observed that the “bonus of $20 given to coolies has been the main stumbling block to the maintenance of order…. One coolie caught buying articles in crews’ quarters and showing resistance was handcuffed & locked up for 6 hours as an example.”

A logbook entry for April 19th notes that CLC interpreter No. 13846 was reported missing the previous evening after the ship left Nagasaki. “Can only conclude that he dressed in European clothes…& went ashore…. Coolie No. 11621 died at 5:30 p.m. from obstruction of the bowels. Reported sick yesterday & put under medical treatment. Agreed with doctor that the best thing would be to keep the body onboard until arrival at Yokohama, as the coolie was sick at Nagasaki & his name, etc., had probably been reported.”

The Empress of Asia reached Yokohama at 9:30 a.m., April 20th and although the labourers were once again lined up for medical inspection, an examination did not follow. Local police were assigned to patrol the wharf to –according to Greenhill–“prevent desertions. Gun police placed at likely places to keep coolies in order.”

Later that day, seven more members of the CLC were brought to the ship. Due to illness, the men had been left behind by another transport. “Agreed to take six (one being still seedy & as he had been down with pneumonia & cold weather is anticipated doctor agreed with me it wasn’t worth risking),” wrote Greenhill. So presumably, that man was left behind.

At midday on the 21st, the ship commenced its transpacific voyage to Canada. “Decided to put body of dead coolie No. 11621 overboard, there being no sign of opposition amongst senior Chinese. Burial [at sea] took place short[ly] after 9 p.m. when deck was clear.”

By the 22nd, noted Greenhill, “a large percentage of coolies [were] seasick.” By the next day, Forbes–the man who suffered an epileptic seizure–was down with pneumonia. On the 24th, labourer No. 13490 was sentenced to two days incarceration on reduced rations after he was found in the ship’s cooks quarters. Rough weather on the night of April 25th made the labourers too sick to attend morning parade on the 26th. Then on the 27th, labourer “No. 11592 died of heart failure due to affection (infection) of the lungs about 5:30 p.m. Burial took place at 8:45 p.m.” Greenhill noted on the 28th that the total number of labourers on board was 2,404–even though the ship had sailed from Weihaiwei with 2,401. However, Greenhill completed his logbook entry for the 28th by stating that labourer No. 11614 died at 3 p.m. that day of “obstruction of the bowels.”

The ship finally reached the William Head Quarantine Station on Vancouver Island at 9 a.m., April 30th. Again, the men were medically examined and it was determined two had the mumps while another had the measles. There were also nine men suffering from what Greenhill described as “non-infectious” ailments. The sick appear to have been landed and exchanged for twelve other members of the CLC. Greenhill noted the transport reached Vancouver via Victoria by 8 p.m. that day.

But shortly afterwards, there was trouble on the Empress of Asia, as noted in Greenhill’s logbook entry for May 1. “At about 8 p.m. a serious fight started between ships’ firemen & coolies. Origin so far as I have been able to learn was owing to a dispute between the sergeant of XV “B” [Company] and a fireman. The former is said to have struck the latter. In any case the firemen all came out into the steerage alleyway armed with iron bars & (I am told) knives. I was informed of the trouble by the orderly officer & went below. Kept two crowds apart, while other officers together with assistance from ship’s officers separated others. Watertight doors were closed & as far as possible parties kept apart. The fire hose was brought into use & police or military telephoned for. On arrival of assistance we were able to get things straightened out. Sentries posted & crew sent up to temporary quarters from which they were cut off from steerage. No more trouble. One man unconscious & several cut.”

Part 2, Crossing Canada with the CLC

On Wednesday, May 2, 1917, the Chinese labourers in Leslie S. Greenhill’s contingent began boarding four special trains bound for Montreal. Everyone was aboard by 3 p.m., but departure from Vancouver was delayed due to an accounting error listing one less man from the total that came off the ship. However, it was concluded that a mathematical error–as opposed to a man missing–was to blame.

As with other CLC movements from Weihaiwei, China, the majority of the men were general labourers led by their Chinese sergeants and assistance in the form of Chinese interpreters. Each contingent also included the various British or Canadian conducting officers and medical staff, and from the West Coast, members of the recently formed Railway Service Guard. It should be noted here that the CLC members had all been assigned a registration or roll number prior to leaving China.

The “first train started at 4.15 p.m. Others to follow at intervals of 45 minutes,” noted Greenhill in his diary. “Went through train with Lieutenant C.R. Watson (officer in charge of first train) at night & took tally of number of coolies. Total found correct (604).”

Greenhill noted two labourers were left behind in Vancouver. Their registration numbers were Nos. 9574 and 11541. He did not give the reason. The British junior officer also noted three other labourers joined the train at Vancouver, Nos. 9221, 9042, and 9085. “Captain Russell joined party travelling in 1st train as medical officer.” Greenhill learned that Captain Russell was to report to him. He also noted that Lt. Watson is in charge of the train and instructed that: “(1) an Imperial Officer was to be present at distribution of food to coolies. (2) No Chinese to enter 2 Tourist cars occupied by officers & guards. (3) All windows of train to be shut while at stations.”

On May 3rd, Greenhill observed that a “Mr. Bird brought a (Chinese) interpreter into the tourist car. “Told him (Mr. Bird) this was against rules laid down. Captain Russell brought (a Chinese) dresser, told him ditto. Later in the day Captain Russell took exception to my giving him above instructions. Said I had no authority over him whatsoever. (This is contrary to verifiable advices from Majors Tite & Munro). Captain Russell most insulting. Said that I had no more right being an Englishman in Canada than a Japanese or Indian. Also that he could turn me off the train whenever he wished. I asked Lieutenant Watson to take up the matter….”

Greenhill’s diary entry for that same day also notes he “issued a supply of cigarettes to Interpreter & sergeants for distribution to those coolies who wished to buy them.”

Shortly after the train reached Medicine Hat, Alberta, on the 4th, a telegram was received stating: “Please note that Lieut. Watson is in absolute command of the train & his instructions are final on all subjects & must be given full obedience. If you desire to have instructions issued to other officers on train you must arrange with Lieut. Watson to do so for you.” The telegram was signed by the “Inspector General.”

That was the same day Greenhill observed “several cases of mumps” among the Chinese. The situation did not improve and making things worse was a lack of bread and the fact that the train was behind schedule. Later that day, while making his rounds through the Colonist cars carrying the Chinese, both Greenhill and Watson discovered that religious tracts were being distributed to the labourers by Mr. Bird. “Asked Lieut. Watson to tell him to stop any religious work until we received instructions from I.G. (Inspector General) at Winnipeg.”

As the train continued to fall behind schedule, Greenhill began to assume that the trip would lose three days between Vancouver and Fort William, Ontario (Thunder Bay). Winnipeg was reached at 9:45 a.m. on May 6 and that was where Greenhill and Watson met up with the I.G., a Major Sefton. “Lieut. Watson had already informed him of the various matters requiring settlement. Major S had misunderstood the information sent him & had been under the impression that the Medical Officer was attached from Canadian transportation services only for the continent. On hearing that he was attached to go overseas he said that undoubtedly Capt. Russell is under my orders & told me so to deal with him if necessary. Major S. explained his misunderstanding of the advices he had received.”

Greenhill’s diary entry for that date also notes: “Things running smoothly at present. Major S. told me that I should deal with matter of religious teachings, so I spoke to Mr. Bird who said he had merely given the tracts to men who were either partly converted or Christian. He had not done & did not wish to do any preaching or converting, etc.”

On the 8th, Greenhill wrote: “All well. Cigarettes all given out. Cases of mumps going on satisfactorily. Scabies (4 cases) require sulphur ointment.” However, he noted, there was no such ointment in the medical chest.

The CLC special train reached Montreal on Wednesday, May 9th, at 2:15 p.m. and the men immediately grabbed their kit and de-trained. “The coolies being marched off in the order in which they were manifested by the C.P.R. to S.S. Missanabie. Embarkation completed by about 7:30 p.m. Food served out.”

However, the situation on board the three-year-old steamer bound for Halifax would soon get out of control.

Part 3, Trouble in the Galley

With embarkation complete, the steamer departed Montreal at first light on Thursday, May 10, 1917. Arrangements, noted Leslie S. Greenhill, were made for two shifts of CLC labourers to act as cooks during the voyage down the St. Lawrence and on to Halifax. The British junior army officer also observed that proper tallies were made for each CLC section of men on board prior to sailing.

“Ship in a very dirty condition as she has no proper staff to keep the place clean,” he wrote on Friday, May 11. “Arranged for each steward of each section to have a staff of Chinese coolies under him, the coolies to be paid by the ship….”

On the 12th, Greenhill noted that the “sanitary squads were working well,” and that “there was good food distribution.” Unfortunately, order was soon replaced by chaos. “Trouble occurred immediately after food had been dealt out in the afternoon. The men came back demanding more (the amt. of rice in each bucket (full) was not enough as it had been served in a form of thick congee & the amount of liquid was much against the men getting a full ration. There was no more rice in the boilers & a time would be required.”

Greenhill noted that “more and more coolies arrived on the scene & could not be quietened. They accused certain sergeants of “squeezing & selling rice (One (CLC) sergeant at a time was supposed to be on duty in the kitchen to maintain order.) They also accused the cooks. The cooks hearing this became restive & came out armed with choppers….but were prevented from getting into contact with coolies. Meanwhile, the glass panels of the door had been broken open with bamboos (a bundle of which had been left about instead of being put in the hold).

“More trouble then occurred in the “Working alley-way:” from which there is an entrance to the kitchen & the whole passage was full of men. Things looked really serious & as we had no other means of quietening them (they had undoubtedly been under-rationed though the full amount was given out by the purser.) I decided to give them a ration of bread which fortunately was lying ready intended for the next day.”

Then, while the men were waiting “for the bread to be brought out the coolies suddenly re-appeared on the scene, coming out of the kitchen armed with choppers, and one (with) a red-hot poker. No damage was done.”

Greenhill noted that “no more trouble occurred, but seeing that the coolies had gained their point by a small show of force, which we were unable to withstand having practically no N.C.Os (non-commissioned officers) of any use, things did not look very hopeful for the future…there seemed to be a fair chance of more troubles occurring.”

With that in mind, Greenhill “asked the Captain to apply for a guard of soldiers to be placed on board at Halifax.

But by Sunday, May 13, a calmer atmosphere prevailed. “Arrived Halifax about 2 p.m., but Captain could not get into communication with authorities.” This was presumably to ask for the guards.

Monday, May 14: “Wrote a report & reasons for demanding a guard.”

On May 16, Greenhill noted that “a guard of 48 men & 2 lieuts (lieutenants) arrived on board at 11.15 a.m.”

Five days later–May 21–at 7:10 p.m., the ship commenced crossing the perilous North Atlantic.

Monday, May 28, 1917: “All well,” wrote Greenhill. “Arranged with Captain that a ration of bread & eggs should be ready for distribution on landing at Liverpool.”

—–

From Britain the men from northeastern China would eventually cross to France and join other members of the CLC–all of them non-combatant labourers assigned to such tasks as unloading ships, stockpiling ammunition, repairing roads, felling trees, and hospital work as orderlies.

Leslie Greenhill went on to serve with a British siege battery at Ypres. He survived the war and returned to Hong Kong where he remained unmarried until he met and wed Edith Kortright of Toronto. On April 26, 1935, the couple and two of their daughters arrived in Victoria, B.C., on the Empress of Asia. Greenhill was asked if he planned to settle in the provincial capital. “I’m not quite decided about this yet,” he told the Victoria Daily Times. “I will spend a week or ten days here and then proceed to Toronto to visit some relatives. Then if I decide to live in Victoria I will return late in July or early in August to take up residence.” (Source: Victoria Daily Times, April 26, 1935, p. 15.)

Leslie Greenhill died in 1955.